Using the Tools in Your Performance Excellence Toolbox: Part 4

Gathering Data

This is the fourth in a series of posts on using performance excellence tools. It covers the reasons for and basic methodologies designed to help you gather baseline data.

Why gather data? There are numerous phrases to explain why:

• Data is king!

• “What gets measured gets done” (attributed to numerous individuals)

• “Without a standard, there is no logical basis for making a decision or taking action” Joseph Juran

• And my favorite – “In God we trust, all others bring data.” W. Edwards Deming

But the basic reason is that without a baseline to work from you do not know if or how much you are improving your process. And without data you can’t determine your baseline.

What is data? “1. factual information (as measurements or statistics) used as a basis for reasoning, discussion, or calculation …” http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/data

Data and information and occasionally even knowledge are used interchangeably, though incorrectly. You are gathering data not information to set the baseline.

So how do they differ? Data is the raw facts about the process (symbols such as numbers). Information is an analysis and configuration of the data (often stated to be achieved by human interaction on data) that makes it useful. Knowledge is the combination and reflection on the information to answer the how of a question.

I have come across some people who use surveys, interviews, focus groups, etc. to “gather data.” To me this is VOC not data gathering since there is very little if any raw facts gathered. Oh well, to each his own.

Now that we have defined data, how do we collect it? First what type of data are you looking for? It must be quantitative in nature. Quantitative data:

Deals with numbers

Can be measured

Examples: Length, height, area, volume, weight, speed, time, temperature, humidity, sound levels, cost, members, ages, etc.

In addition to quantitative data you can use Qualitative (note in addition to not in place of). Qualitative data:

Deals with descriptions

Can be observed but not measured

Examples: colors, textures, smells, tastes, appearance, beauty, etc.

Three things to remember when gathering data:

• KISS it (Keep It Simple Stupid) unless it is absolutely necessary, e.g. high complex manufacturing process), keep the data gathering as simple as possible

• 3 bears rule

1. Not too little

2. Not too much

3. Just enough

• Verify it – is it trustworthy, reliable, repeatable

You need to be aware that you don’t become infected with the paralysis by analysis virus. The first signs appear during data gathering and include the irresistible urge to just get one more piece of data.

The basic way to gather data is by using a data gathering worksheet. These are customized to your specific needs. I generally use an Excel Workbook for by data gathering. This allows a great deal of flexibility and you can add as many worksheets as you need to tailor your responses.

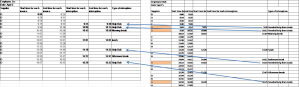

For example suppose you wanted to collect data on the time it takes the Accounts Payable staff of 10 to process invoices.

Determine the sample size and duration (number of cycles).

• Sample size – 10 employees

• Duration – 5 weeks (each day is a cycle)

You set your data point requirements. In our case they are:

• Employee

• Date

• Supplier

• Start time for each invoice

• End time for each invoice

• Start time for each interruption

• End time for each interruption

• Type of interruption

Figure 1 Data Gathering Worksheet

Each employee will complete a worksheet each day during the data gathering cycle.